How to Make Money with Philosophy?

Yes, I am serious.

It’s not a joke

I understand if you thought this was a joke or a clickbait headline. It does sound like one, I give you that.

But, this time I’m serious. I am a professor of philosophy, and I’m here to give you an honest answer to this question:

Can you become a professional philosopher and make money with it?

I’m not an influencer, and the point of writing this is not to suggest you should or shouldn’t pursue philosophy as a career. I’ll not judge you if you decide to go that way and join the “Dead Thinkers Society”. Also, I will not try to sell this career joice as something cool and trendy.

Because it’s not.

I have an ulterior motive, though. I want you to think about your life and career choices like a decision theorist would. This doesn’t mean you should pursue life happiness like a robot, weighing options as if they were stocks on Wall Street.

But, it does mean you should gather data, calculate your chances, combine them with desired outcomes, and reach an analytically sound conclusion about anything in life. Including philosophy.

How to become a philosopher?

Let’s start by clearing out the question of how can one become ‘a philosopher.’

There are four different ways.

First, you could go to the graduate school.

Second, you could go to the graduate school.

Third, you could go to the graduate school.

And fourth, you could go to the woods. Which I don’t recommend.

Basically, if you want to wear the mantle of a philosopher, the only option nowadays is to take the academic route. Gone are the days when you could wander from city to city, preach to youth, and make a decent living. Almost all philosophers today teach at a university.

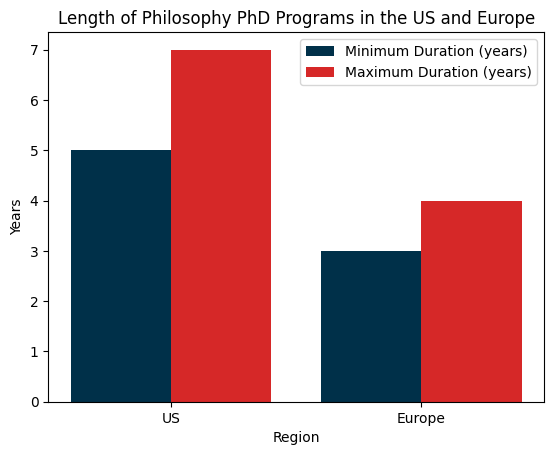

Once you’re in graduate school, there are two levels, like in a video game: the Master and the Ph.D.

How long does it take you to complete them? Masters, in the U.S., takes about two years, and in Europe a bit less than that. Ph.D., in the U.S., can take you between 5-7 years, and in Europe between 3 to 4 years.

It is important to consider this time as your investment in this career choice. If you choose this path you may spend the next decade in school (and if you don’t get a stipend, you’ll also spend a lot of money getting the degree).

And what do you do in graduate school?

Well, of course, you learn philosophy. A lot of it. This theory. That theory. This guy makes this claim. The other guy makes another claim. Who’s right? I don’t know.

Graduate school does what it says: it schools you. Teaches you theory, but nothing much else. It assumes you want only theory because it is designed to train future professors of philosophy; that is academics.

Today this is the only way to exist as a philosopher: to become an educator.

Cool, you say.

The job market

If that’s something you’re looking for, once you’re done with your degrees, you enter the academic job market. You prep your C.V., prepare your letters of recommendation, this statement, that statement, a urine sample, and a Hail Mary.

And then ….

You hit the first wall.

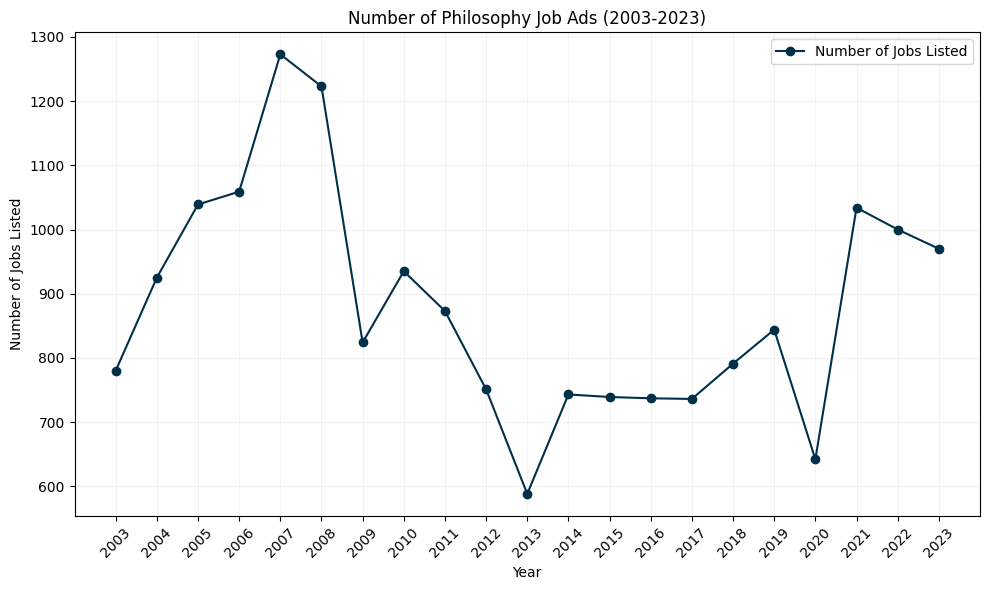

You realize that there aren’t many academic job openings around. Here are the data for the last two decades (U.S. only):

Mind you, these are the number of job postings, not actual jobs awarded. Some of the postings could be duplicates.

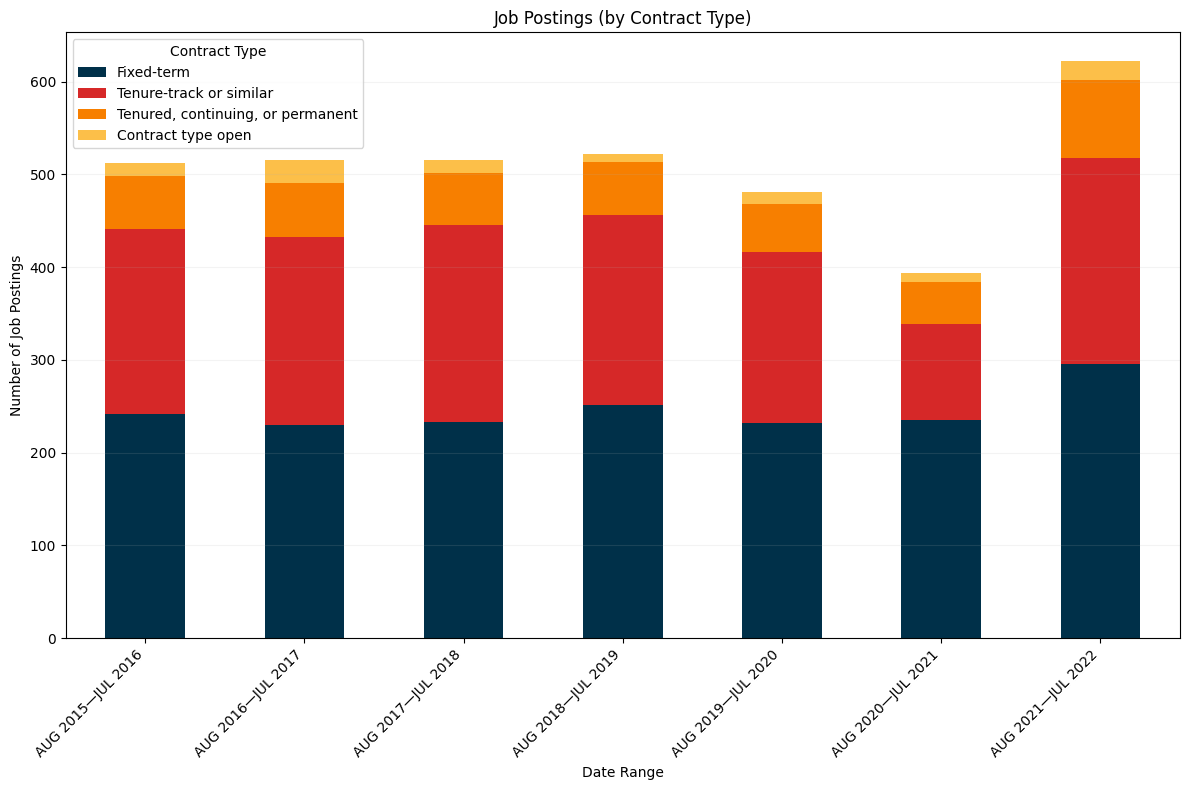

Here are the data on the jobs awarded and their types:

As you can see, most of the jobs are fixed-term ones. This means that they are terminated after a year, two, or slightly more.

And they’re seasonal. Job postings start appearing around September, picking up in November, with deadlines later in the year.

And that’s it. The review of candidates will last for a couple of months, followed by interviews in early Spring, and ending with offers in April or May.

Then, you hit the second wall.

You don't get any offers.

Very often you don’t get any interviews either.

You get nothing.

Zero.

Unless your Ph.D. degree is from the top university in the U.S. or Europe (think Harvard, Yale, Stanford, or Oxford, Cambridge, and similar), you realize that your degree is not enough.

To compete, you have to publish articles in peer-reviewed journals, muscle up your C.V., and buy a tweed jacket and a pipe.

One option, while you wait for the next round of openings next Fall, is to do a post-doc.

This is a temporary research position at a university, lasting for a year or a few. You go back to school to read, publish, drink, and try your shot next year.

And the year after that.

And the year after that.

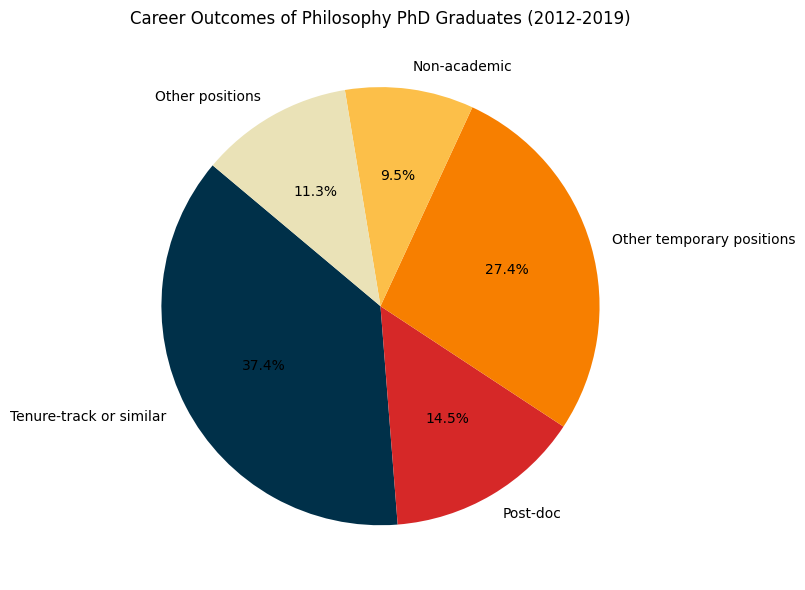

The reality is that there are only a handful of full-time academic jobs to go around, and there are plenty of candidates.

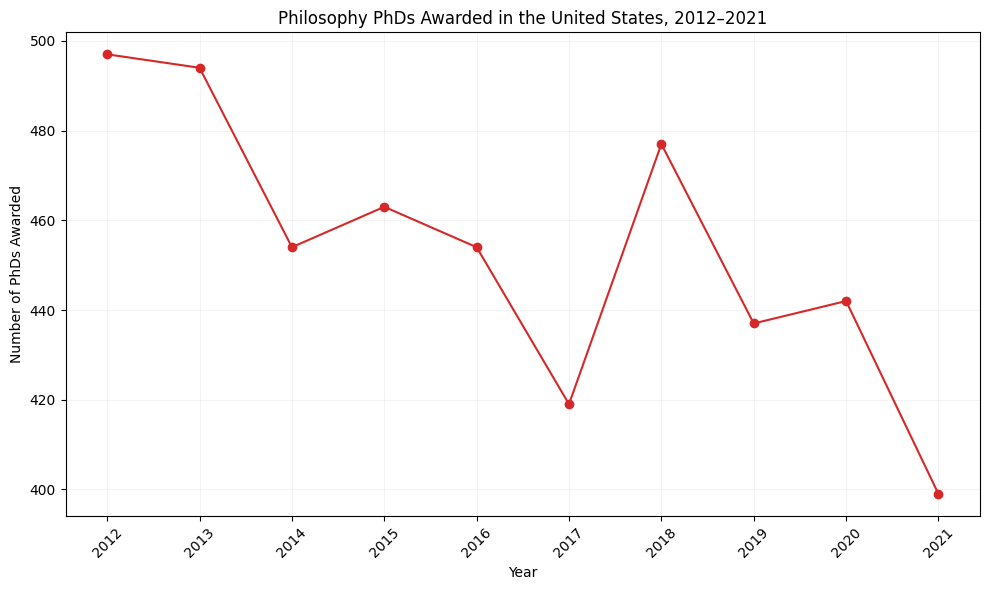

In the last ten years, in the U.S. alone there have been on average 400-ish Ph.D. graduates every year and only 200-ish tenure-track (full-time) jobs.

Check the data for yourself:

If all of these graduates decide to stay in the academic job market, then every year you’re competing not just against your cohort of graduates, but also against the survivors of the previous cohorts, who failed to score a job in previous years, and the upcoming cohorts of graduates. And they’ve spent those years building their C.V.s, publishing research, and buying up all reserves of tweed for themselves.

If by some miracle you manage to land a full-time job and remain a (relatively) normal person, you get into another video game with levels. First, you become an Assistant, then an Associate, and then a Full Professor. Each stage comes with some prestige and a slightly bigger salary.

How much money we’re talking about?

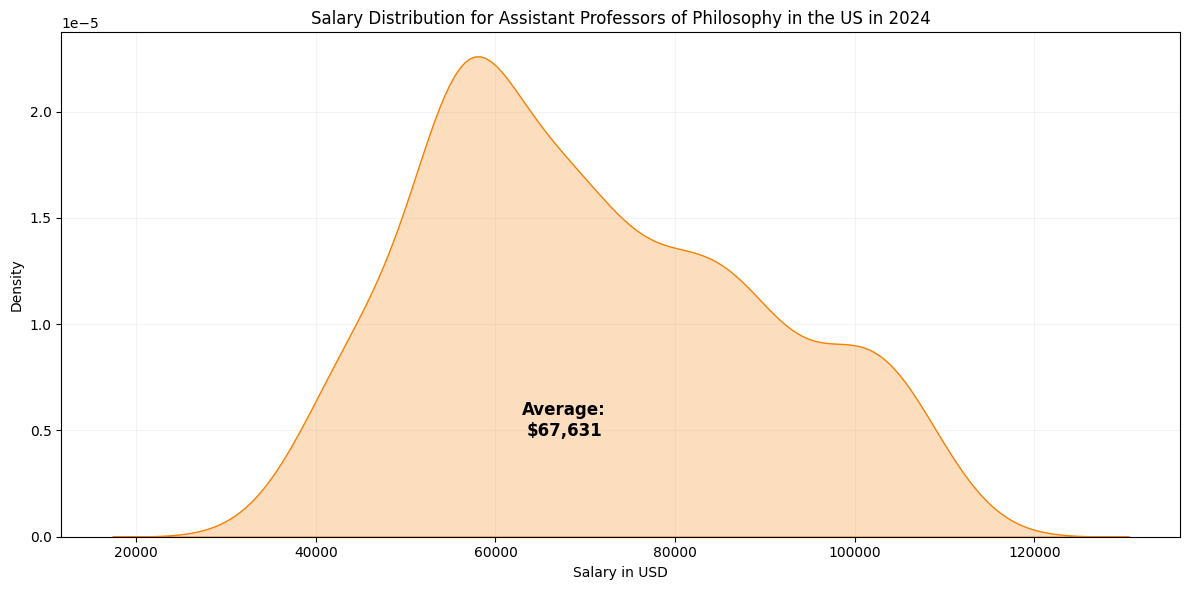

In the U.S., the average (median) salary of an Assistant Professor of philosophy is a staggering amount of:

…

…

…

$67,631.

Annually.

Mind you, this is the average. The salaries can range between $34K at crapy schools in the middle of nowhere, to $166K in fancy schools like NYU, Stanford, or similar.

Here’s the distribution so you can see more:

If you defeat the big boss and reach the final level of Full Professor, you may be lucky to cash in a hefty $200K or so.

And that’s probably the ceiling of the wealth you can make as a professional philosopher today.

Not a bad life, if you make it

It’s not a bad life to be an old and gray-haired philosopher. You sit all day, stroking your cat, and ponder about the universe. You teach a bit, write when you can, drink some, watch Netflix, and go to sleep.

And then you die.

But, how likely is it that you will survive the hunger games of academia and reach the Philosophical Valhalla?

Not very likely.

Let’s try to calculate it by developing a simple probabilistic model.

Imagine you are one out of 400 philosophy Ph.D. graduates in some year (we can take 2021 as the most recent one for which we have reliable data) in the United States. That year, there were around 200 tenure-track philosophy jobs.

If everything else is equal (we’re simplifying here very much), then the chance of you landing this job can be calculated easily, like this:

Probability is a concept we use to quantify (specify) our uncertainty about something. It has very simple foundations: you find the probability of something occurring by dividing the number of possible worlds (scenarios) in which that something occurs by the number of all possible worlds (including the scenarios in which it doesn't occur). Here, we take the number of jobs you could get and divide it by the number of all candidates for those jobs (including you and everybody else), which is a proxy for scenarios in which other people get those jobs too.

With the numbers, the probability of landing a job in the first year on the job market comes down to:

So, in the simplest and most charitable scenario, your chances of getting a stable university job teaching philosophy after you graduate are the same as flipping a coin.

Of course, the model should be made more complex than this. If each year only half of the candidates get a job and next year the other half reapplies to the new positions, then next year (presuming you did not get it in the first year) you’re competing not just with the remains of your cohort, but also with the one that graduated a year after you.

So, presuming that the graduation and job numbers remain constant next year your probability is:

The year after that, you’re competing with more cohorts, so the probability of landing a job comes down to:

Of course, this is a very simple model, which assumes not just that the numbers are constant, but many other things. It could be made even more complex, and take into account the exact numbers for each year, as well as other information, like the candidates’ publication record, the number of graduates from schools fancier or less fancy than yours, the attrition rate (the number of those who leave the job market after being unsuccessful), or the job fit (the alignment of your specific expertise and the job requirements).

I also omitted one gigantic data point, because it is hard to get estimates: the number of applicants from other countries applying to job postings in desirable locations, like the U.S., or Canada. I once sat on a hiring committee for 3 tenure-track philosophy job openings at a small college in the Northeast, and we had close to 300 candidates from all over the world.

(I am also one of such graduates from Europe who applied to U.S. academic jobs.)

So, this is a very simple and optimistic model. But, it should be enough so you get the point: the picture is not rosy.

I took the actual data from the 2015-2021 to calculate the probability of landing a job in the first seven years after graduating. Here’s the chart:

The alternatives?

Ask anybody in the field of academic philosophy today, and they will confirm the dismal picture of the job market that these graphs show.

There could be many reasons behind this that we could debate about, but we don’t have to. It is enough to resort to the basic principles in economics: supply and demand. There is an oversupply of philosophy Ph.D.s and there’s shrinking demand.

So, in case you’re not deterred, what are the alternatives?

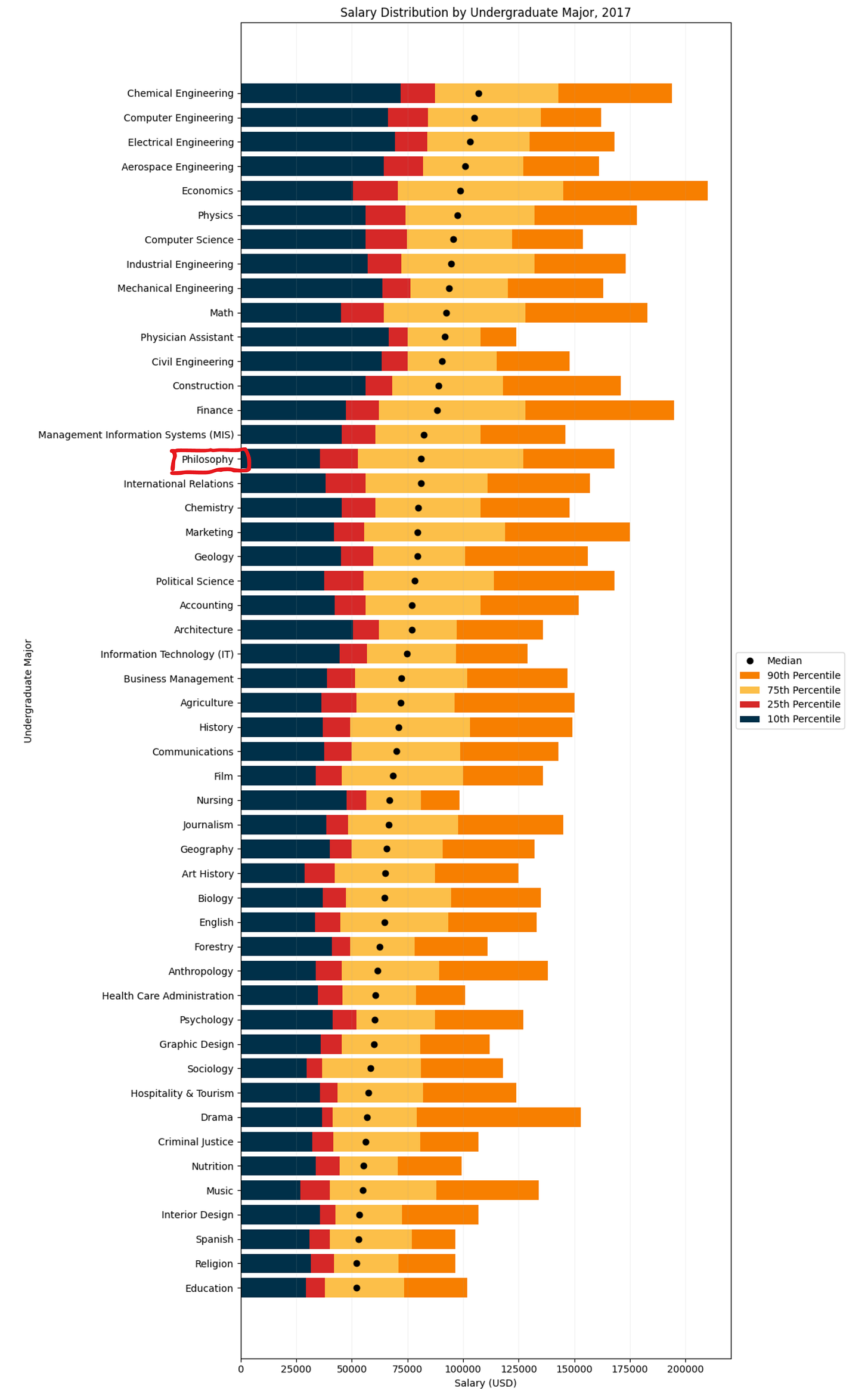

First, none of this doesn’t mean you shouldn’t study philosophy. As a matter of fact, undergraduate philosophy majors tend to earn more money today than graduates of other majors in all the humanities, and some non-humanities too, such as accounting, or health administration.

Check this:

This means that if you study philosophy as an undergrad, you’ll likely find a well-paying job. But, the catch is that the job will probably not involve philosophy at all. Philosophy is great for helping you develop good critical thinking skills, which you will then apply to some other field.

And that’s good. Everybody should learn how to be a good critical thinker, and philosophy might help. But, it doesn’t mean you should get a Ph.D.

Second, if you’re still intent to get a graduate degree, then the only possible alternative to razor-thin chances of academia, is to become some sort of a ‘popular philosopher,’ like Jordan Peterson, open social media accounts and philosophize online every day.

You may even become a meme.

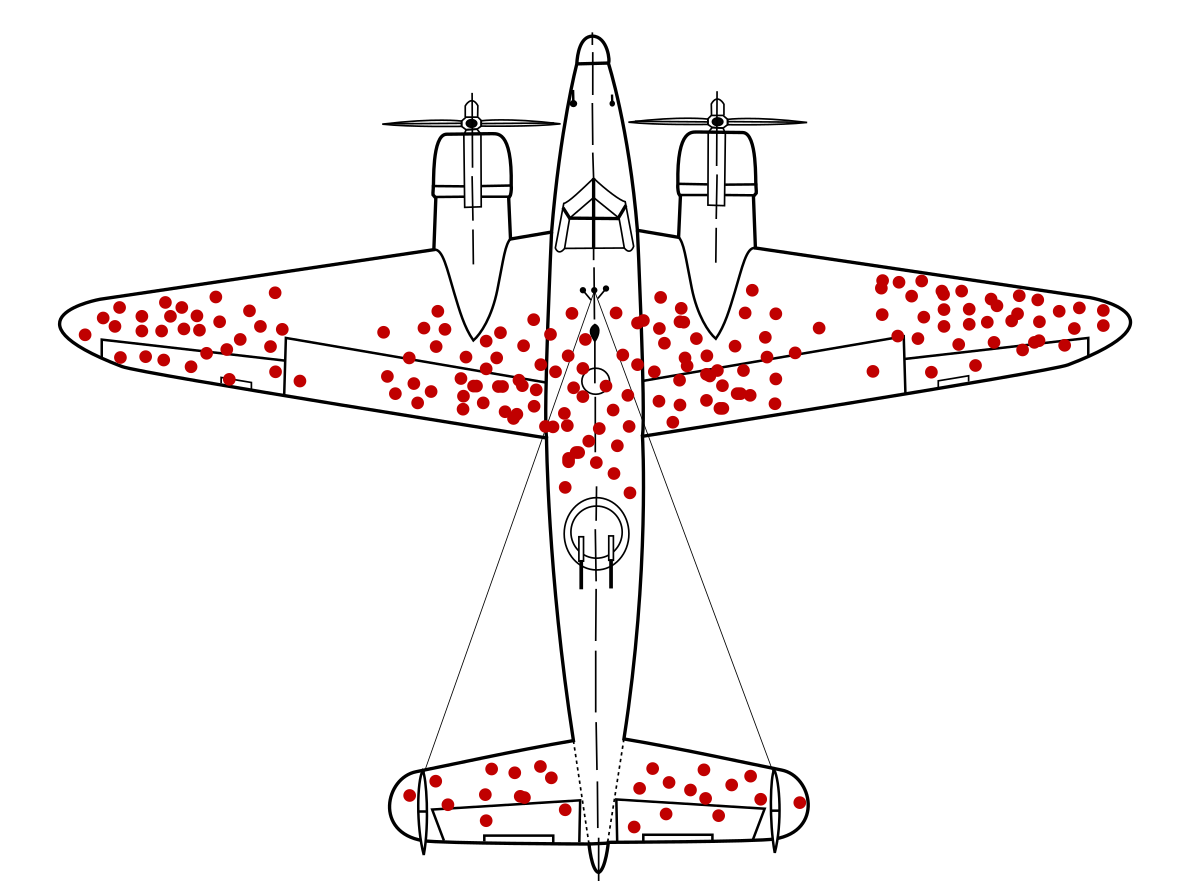

If you really want to think, write, and talk about ideas all day, then you can become a philosophy influencer. I hear TikTok is hungry for philosophical hot-takes. Good luck with that and don’t forget to consider something called a survivorship bias: the fact that there are philosophers on YouTube who make money making videos doesn’t mean that anybody who tries to do that will succeed. Probabilities apply here too.

Conclusion

Instead of a wise conclusion to this depressing tale about philosophy and money, I have homework for you.

Whatever your field of study or interest is, probability significantly influences your chances of success. If you want to approach your future analytically (read: seriously), you should gather data and make your own analysis, similar to the one you’ve seen here.

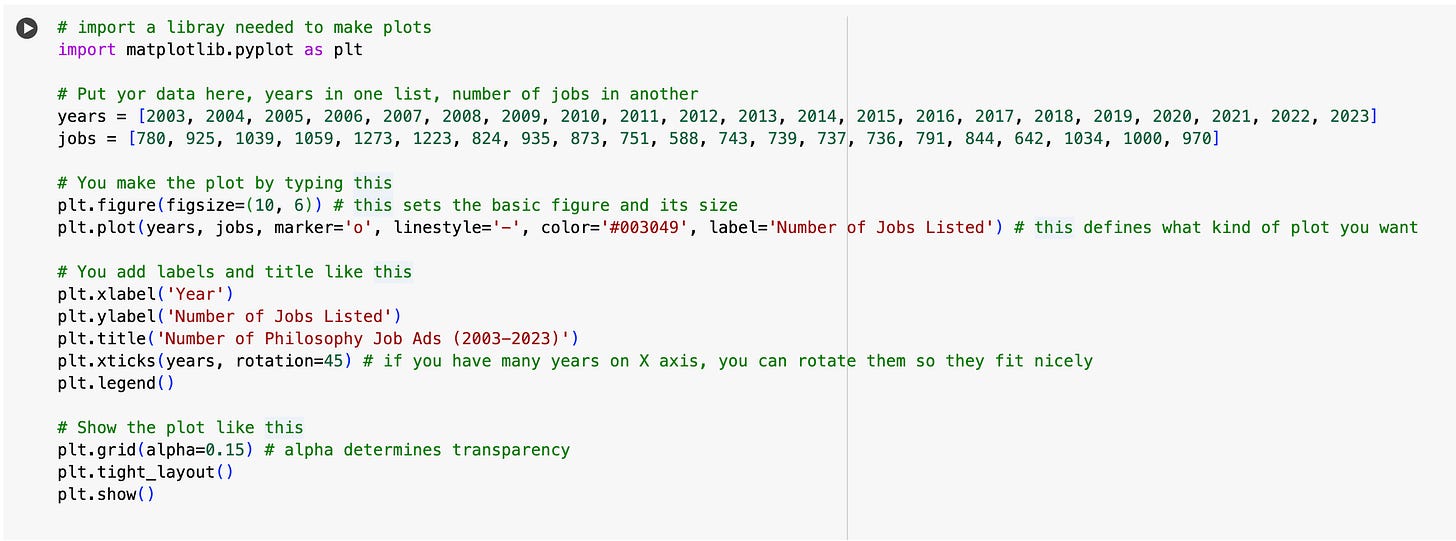

Python can help you with this. Here’s a simple code from Google Colab that will allow you to make a line plot with the job data that you collect in your field:

If you want to copy-paste it, here it is:

# import a libray needed to make plots

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Put yor data here, years in one list, number of jobs in another

years = [2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023]

jobs = [780, 925, 1039, 1059, 1273, 1223, 824, 935, 873, 751, 588, 743, 739, 737, 736, 791, 844, 642, 1034, 1000, 970]

# You make the plot by typing this

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6)) # this sets the basic figure and its size

plt.plot(years, jobs, marker='o', linestyle='-', color='#003049', label='Number of Jobs Listed') # this defines what kind of plot you want

# You add labels and title like this

plt.xlabel('Year')

plt.ylabel('Number of Jobs Listed')

plt.title('Number of Philosophy Job Ads (2003-2023)')

plt.xticks(years, rotation=45) # if you have many years on X axis, you can rotate them so they fit nicely

plt.legend()

# Show the plot like this

plt.grid(alpha=0.15) # alpha determines transparency

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()Don’t forget that the lines starting with the # are comments that explain what each part of the code does.

Now, the homework:

Exercise 1: Collect data about job openings in your field in the last several years. Put them in a list and plot it using the line plot example code given above. Find the data about the numbers of graduates in your field and plot them too. Compare the two plots. Draw conclusions about your chances of success. Write a short paragraph explaining your conclusions and pointing out to some other factors that influence these chances that cannot be easily quantified and modelled.And, that’s a wrap!

By all means, if you don't actually care about philosophy, become an academic. Otherwise, here's most of the answers, for free: https://kaiserbasileus.substack.com/p/metaphysics-in-a-nutshell

Academic credentials prove compliance, indicate knowledge, and say nothing of understanding.